Romalina by Clarice Vaz - A Book Review

- Heta Pandit

- Jul 26, 2025

- 4 min read

Sometimes it is hard to review a book when it has been written by a friend. On the other hand, when you are a writer yourself, every other writer is a friend/colleague/fellow writer. Clarice Vaz is much more than a fellow writer. She’s my gao bhoin or village sister, a sister bound simply by the fact that we live in the same village. When Clarice talks about the hardships faced by the Uganda returnees who left with too little too late and came back to live in Goa, I can feel her pain. When she describes how the Afrikanders dressed differently, spoke Swahili and ate English food at home, I know how they must have felt, alienated in their own land.

In her book ROMALINA, a book title bearing the heavy burden of her grandmother’s name, Clarice has become a daughter, a granddaughter, a child. She speaks in a child’s voice when she describes her growing up years. Her parents, grappling with a Goa they could not cope with, were in a bind while she and her sisters, at an accommodating age, were taking all the newness in their stride. It was as if there were two sets of people in two different countries under one roof.

Clarice speaks of her ancestral home in Moira with feeling. She tells us, “As I took long strides, it was as if I was meeting an old friend who was equally delighted to see me”. On the other hand, there was a storeroom that her grandmother Romalina kept. A peek into that storeroom was the stuff of any child’s nightmare. This is where her grandmother would store pickles, masalas, salt, vinegar and all sorts of things that would come in useful someday. When her companion, Topsy the cat went in chasing mice and other interesting things (dead/alive, animate/inanimate) there were no complications. For, as Clarice says, “Topsy did not think of preserving rats in brine, vinegar or salt for a rainy day”.

There was also the incident of the large hole in the meatsafe and the hissing (real or imagined) sound that emanated from it. Clarice describes, with wry humour, how everyone went into a panic when they thought there might be a snake in there. This was indeed compounded by the fact that her grandmother was quite firm in the belief that you had to “watch the snake carefully for the number of lines below its hood. This tells you the number of hours you have left to live, should you get bitten. One line means an hour… two means two…” I do hope all our Goa herpetologists Aaron Lobo, Nirmal Kulkarni, Rahul Alvares are reading this review!

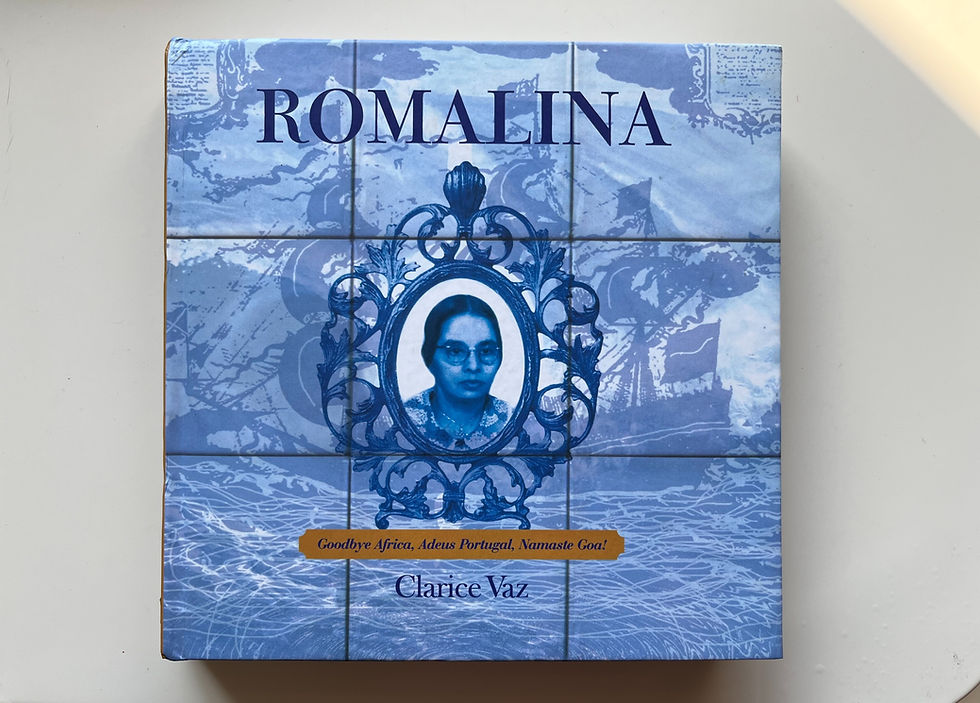

Bina Nayak’s illustrations and book design are an astounding combination. Bina, also a fellow writer, has obviously taken pains over reading the book and tapping on the most poignant bits from the bit to illustrate. The illustration of Clarice sitting on the gatepost as a child and pretending she was a finial is, in my opinion, worthy of being made into an azulejo tile. All the illustrations are done in the beautiful azulejo tile fashion but this one obviously tops them all.

The Pink House, the house where her ancestors once lived, as Clarice says, is a house that you can read as a book. “Walking into this house feels like reading an anthology filled with stories, memories, echoes of voices, tear drops, despair, a hearty ring of laughter, flaring tempers”. In other words, life. And, as the scorched memories of her Africa days were being replaced by the warm, vibrant world of sounds and smells, there were stories to savour. Of the ubiquitous pão, the Goan bread, Clarice says, “The pao was what I liked. This small square piece of bread was just love made edible.” Those words, to me, are like a well-buttered piece of bread at the breakfast of life in Goa. How bread used to be delivered in the past and how that has changed since Romalina’s childhood is Goa’s history in a capsule.

Clarice’s treatment of architecture in the book is unique and extraordinary. As someone who writes and speaks about Goan architecture, this is a learning experience.She describes the architecture of both Uganda, where she migrated from and Goa, where she was trying to fit in, in rather subtle ways. “The church in Africa had a different look…” she says and I recommend this book to architecture students. Going for Mass in the Goan village (first Moira and then Saligao) is brief but it is also a very in-depth description of life in a Goan village. Duality, she says, came as second nature to her grandmother as it must be for most people in the villages of Goa. Romalina, she says, dressed immaculately for Church, prayed in Latin, wore a dash of make-up and mingled with guests in her sala with impeccable grace. Once in the deeper recesses of her home, however, when she was in the back rooms and the kitchen she would curse like a trooper if she couldn’t find something that she was looking for!

In a sentence, a Goan is like a banyan tree. Her roots are there for all to see.

Comments